Disney's Distribution, and Behind Buffer's New Homepage

Alfred Lua / Written on 10 April 2020

Hello,

This is my weekly private letter on marketing and distribution models. When relevant, I'll also share numbers and discussions on Buffer projects to give you an insider look at the daily life at a tech company. In this private letter, I'll be talking about the project to update our homepage.

Disney's Distribution

First, a recent news: Disney reported 50 million paid Disney+ subscribers worldwide after just five months since the launch:

Within five months of initial launch, Disney Plus has signed up 50 million paid subscribers worldwide, the media company said.

Disney last reported 28.6 million Disney Plus paid subscribers as of Feb. 3, meaning it’s packed on more than 21 million net new subs in roughly two months...

The 50 million figure is well ahead of the company’s own forecasts — and those of Wall Street. Disney, in unveiling the road map for the streaming service almost exactly a year ago for investors, had pegged a goal of 60 million-90 million global subs by the end of fiscal 2024 (Disney’s fiscal year ends in September). Disney Plus may hit that target four years early.

And this is even before Disney+ is available in Western Europe, Latin America, and Japan.

There are two interesting distribution strategies I want to highlight here:

First, partnership is a powerful lever to pull for distribution. Part of Disney+'s growth can be attributed to Disney's partnership with Verizon. As the exclusive US wireless carrier partner for Disney+, Verizon has been offering 12 months of Disney+ to all new and existing 4G LTE and 5G unlimited wireless customers — for free. According to then-CEO Bob Iger, about 20 percent of Disney+ users came from Verizon (which is much smaller than I had expected). Partnering with the second biggest telco in the US by market share gave Disney access to millions of potential customers right away. In practice, that likely meant emailing millions of Verizon customers about Disney+ during the launch and sending followup emails and letters over the next few months. Partnering with a non-competing company for distribution feels like a strategy that more tech companies should adopt but I have not seen many myself. Content partnership seems more common likely because it's easier to coordinate. If you know of any similar partnerships from tech companies, let me know.

Second, Disney+ in itself is a distribution channel — for Disney's other businesses. Disney is likely making a loss through the partnership, at least for now [1]. But that seems fine if you look at Disney+ as part marketing expense, part new business line, just like other parts of the business.

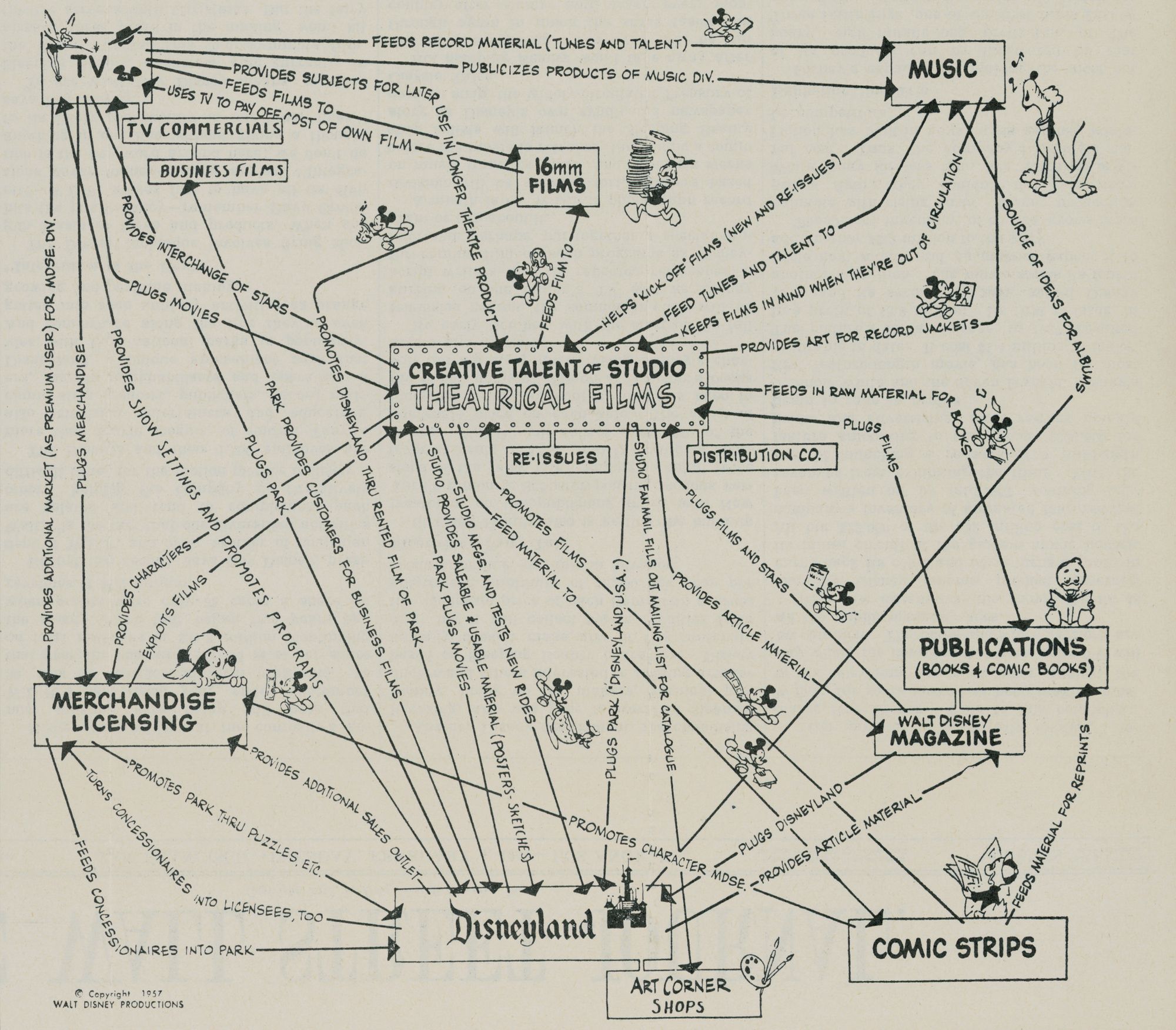

The Disney business map by Walt Disney

Disney+ is a new distribution channel that Disney fully controls. As I tweeted, "Disney+ feels like a marketing tool for Disney’s parks, resorts, and merchandise. Parents pay for Disney+ for their children, who will then ask to buy toys and visit Disneyland." The unique thing is this marketing expense might eventually become a negative cost (i.e. profitable).

The Disney business map by Walt Disney

Disney+ is a new distribution channel that Disney fully controls. As I tweeted, "Disney+ feels like a marketing tool for Disney’s parks, resorts, and merchandise. Parents pay for Disney+ for their children, who will then ask to buy toys and visit Disneyland." The unique thing is this marketing expense might eventually become a negative cost (i.e. profitable).

What other distribution strategies and takeaways can you draw from Disney+? I'm keen to learn from you.

Now, onto this week's update:

Behind Buffer's new homepage

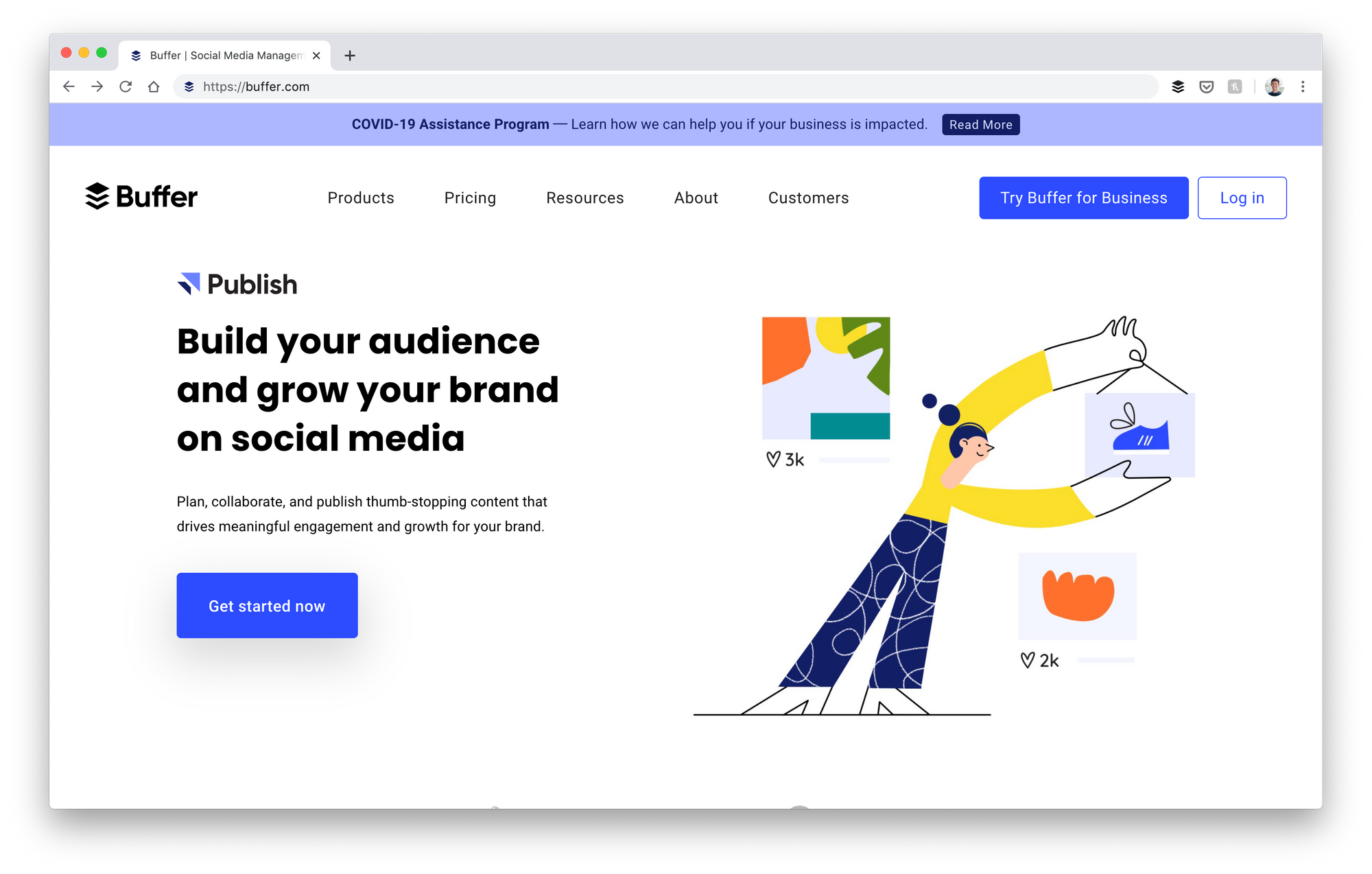

If you visit buffer.com now, you'll see our new homepage, which we just shipped two days ago.

In the industry, Buffer is most well-known as a social media scheduling tool. That was great a few years back but not now. Over the last two years, we have been building new tools to help businesses build their brand and connect with their audience on social media. For example, Analyze (which I helped launch last June) is our second standalone product, a new social media analytics tool. We are also working on a social media engagement tool for marketers who want to connect with fans of the brand.

In the industry, Buffer is most well-known as a social media scheduling tool. That was great a few years back but not now. Over the last two years, we have been building new tools to help businesses build their brand and connect with their audience on social media. For example, Analyze (which I helped launch last June) is our second standalone product, a new social media analytics tool. We are also working on a social media engagement tool for marketers who want to connect with fans of the brand.

But most marketers still see Buffer as simply a social media scheduling tool.

People have been cancelling their Buffer subscription because they wanted analytics and thought we didn't offer it. We wanted to change that misconception.

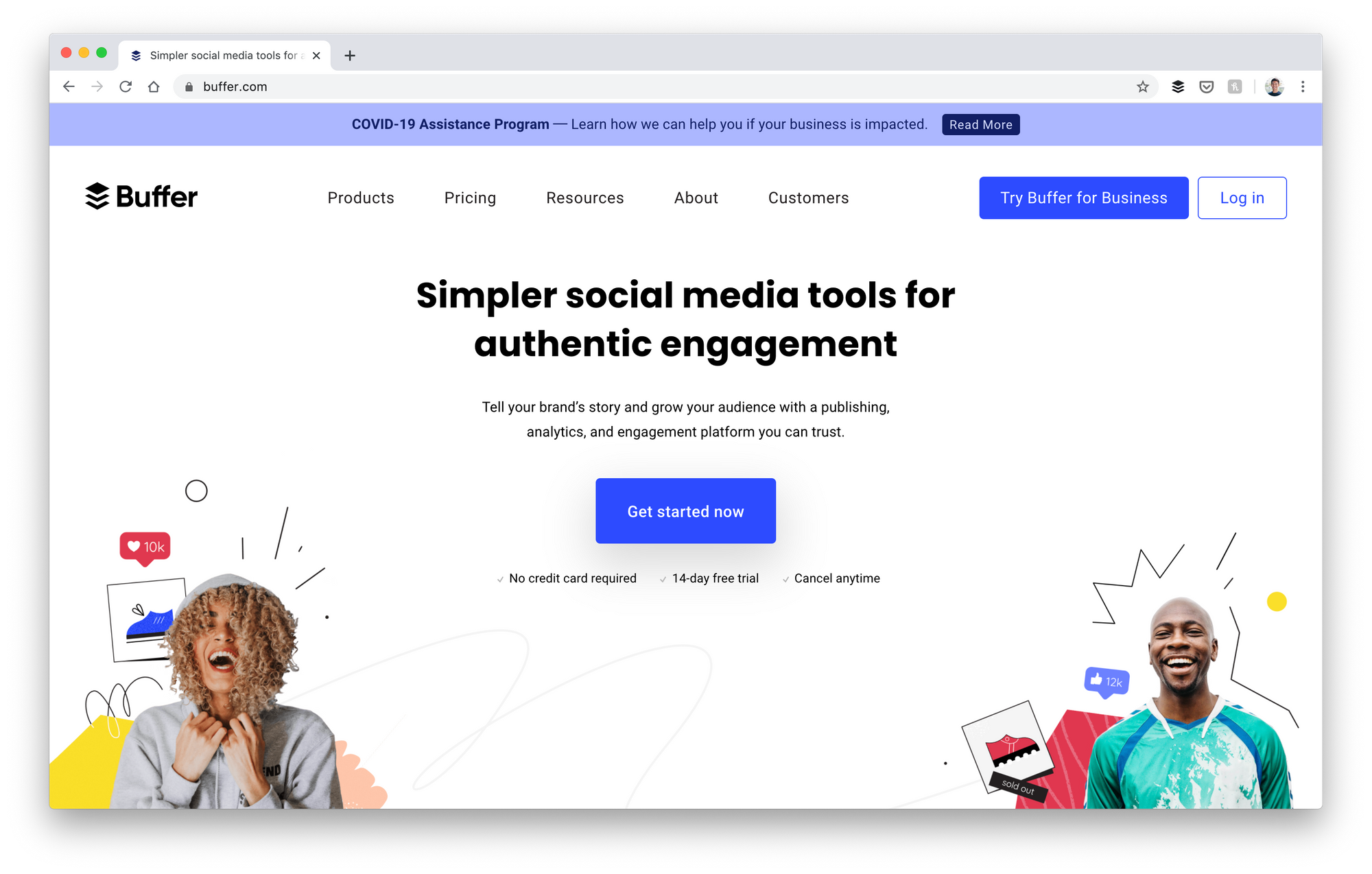

A good place to start is the homepage because it receives the most amount of traffic and sets the initial impressions in the visitors' mind. The homepage was still featuring our flagship product, Publish, because that's where most visitors would see and sign up for Publish, which generated the bulk of our revenue. Since it could have a significant impact our revenue, we wanted to be careful changing the content on the homepage. By featuring both Publish and Analyze on the homepage, we could increase the signups for Analyze but also reduce the signups for Publish. To measure the impact of a change, we ran a two-week A/B test [2]. Half the traffic saw the original homepage, half saw the new design.

The original homepage

We waited 28 days after the test before analyzing the results [3]. We looked at the number of trials and subscriptions started for the two products, the number of customers who subscribed to both products, and the amount of Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) generated, by the control and variant groups. The results were exciting. We found that users in the variant group started more trials and subscriptions for Analyze and more users subscribed to both products than those in the control group. Most importantly, our past data have shown us that customers who subscribe to both products have higher lifetime value than those who subscribe to only one.

The original homepage

We waited 28 days after the test before analyzing the results [3]. We looked at the number of trials and subscriptions started for the two products, the number of customers who subscribed to both products, and the amount of Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) generated, by the control and variant groups. The results were exciting. We found that users in the variant group started more trials and subscriptions for Analyze and more users subscribed to both products than those in the control group. Most importantly, our past data have shown us that customers who subscribe to both products have higher lifetime value than those who subscribe to only one.

We have a winner.

The new homepage design, we know, will help shift our positioning and now has shown favorable financial outcomes over the original homepage. We rolled it out as soon as possible.

But positioning is never done. The homepage is never done.

That's because the product evolves (or at least it should). Market conditions change. Customers' preferences change.

We are in the process of combining the various products into a single product. We call it One Buffer internally. We learned that for social media management, marketers prefer using a single product with publishing, analytics, and engagement features to using multiple products, each for a job. Offering multiple products also creates unnecessary confusion for prospects, especially when others in the market are offering all-in-one solutions. We will likely be changing out homepage again in the next few months. Keep an eye out for it.

If you have any questions about our new homepage, I'd love to try answering them.

Talking about changing market conditions, I wrote a Twitter thread on how Basecamp changed their homepage to match what many teams are looking for now:

Basecamp updated their homepage to focus heavily on working remotely as a team as many teams now work from home and are looking for a collaboration tool. pic.twitter.com/tQL0488X1H — Alfred Lua (@alfred_lua) April 9, 2020

Do you know of any other tech companies that have recently updated their homepage?

[1]: Disney+ costs $7 per month while Verizon is paying Disney about $4. This means Disney is paying about $36 ($3 per subscriber multiplied by 12 months) to acquire each customer. A portion of the customers will not continue subscribing to Disney+ after the free 12 months so the cost of acquisition will be higher. Assuming 20 percent of the customers churn, the cost of acquisition will be about $45. To cover this cost (excluding other marketing expenses), each customer has to subscribe for at least another seven months.

[2]: The length of the experiment is two weeks because of two reasons. One, we see consistent fluctuations in signups and subscriptions throughout the week (much fewer people sign up or subscribe on the weekends) and we wanted to account for the fluctuations in the experiment. The analysis won't be accurate for forecasting if we used an eight-day period because that will include, say, two Mondays. Two, the sample size of the experiment has to be large enough for the results to be accurate and reliable. Matt Allen, our data scientist, calculated that two weeks would be sufficient.

[3]: Why 28 days? Our data team discovered that the majority of our customers would have subscribed by the 14th day after the end of their 14-day trial. If someone hasn't subscribed by then, it's likely they won't subscribe at all. For people who started a trial on the last day of the experiment, we wanted to give them 28 days (14 days of trial plus another 14 days) before we analyzed the results. This allowed us to account for as many subscriptions as possible without waiting too long because we'll never know when everyone has made a decision to subscribe or not.