Don't Mistake Freemium as Just a Marketing Strategy

Alfred Lua / Written on 05 June 2020

Hello there,

Earlier this week, I shared what I learned about OKRs from John Doerr's Measure What Matters. If you plan to adopt OKRs, I would recommend reading beyond articles that cover the basics of OKRs. I'm hoping my notes are a good place to start.

Weekly Notes are available to paying subscribers only, and you can get a subscription here.

Today, I want to discuss freemium.

Freemium as a growth lever

Providing a free plan with limited features and paid plans with more features, in other words freemium, is very common in the SaaS space now. Even public listed companies like HubSpot, which has relied mostly on an inbound marketing and sales model, has adopted a freemium model.

The most common argument for freemium is that it is a great acquisition strategy.

I saw this firsthand at Buffer. Freemium has enabled a lot more people to use Buffer than if we didn't have a free plan. When they experienced how easy it is to use Buffer to manage their social media, they recommended it to others. More people try Buffer, and it compounds. Freemium can also be better than free trials because users on the free plan could be using Buffer for years and recommending us for years (and they do!) Free trials ends in seven, 14, or 30 days and the word-of-mouth effect stops if they don't subscribe.

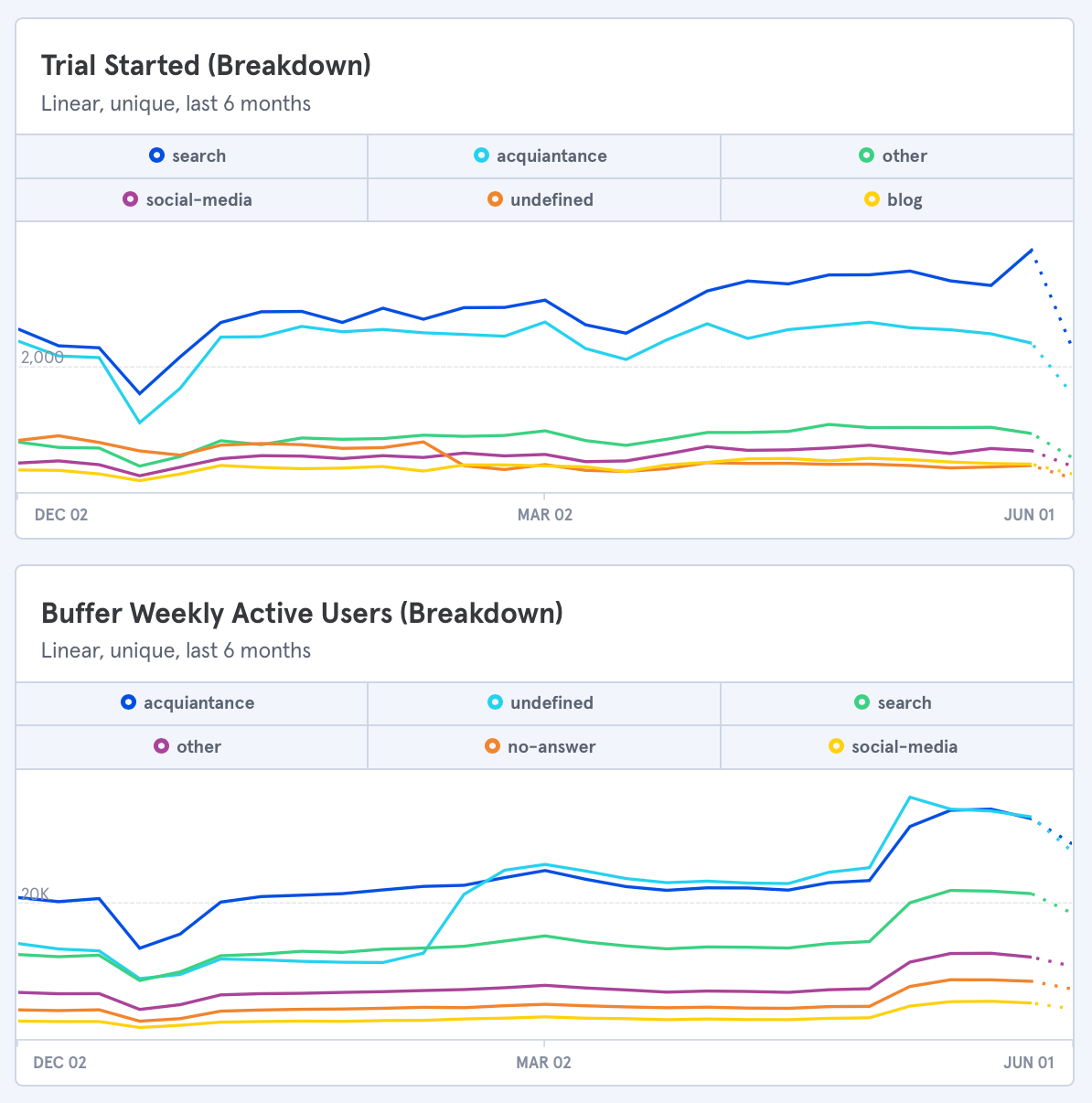

This is powerful because word-of-mouth recommendations are even better than our own marketing. It is the most trusted source of advertising according to Nielsen's | reports. Our data also proves this. Word of mouth is currently our second-best acquisition channel (after search), and users who were referred by their friends are the most active among all our users.

That's why I firmly believe freemium is a great acquisition strategy. When we were simplifying our free plan, I even wrote to our CEO Joel Gascoigne to share my concerns on the impact on growth.

That's why I firmly believe freemium is a great acquisition strategy. When we were simplifying our free plan, I even wrote to our CEO Joel Gascoigne to share my concerns on the impact on growth.

But after five years at Buffer, I learned that freemium affects more than just marketing and acquisition. It impacts several other areas of the company and should not be made as just a marketing decision.

It should be considered under the company strategy.

Freemium impacts customer support

In our initial years, we were able to support all our free and paying users well. The quality of support also contributed to the level of word-of-mouth recommendation we were getting.

In 2014, we had an ambitious vision for our customer support:

Here’s how the story unfolds in my head: It’s 2016. Joel is on stage giving a talk about Transparency and Happiness in the workplace at Tedx San Francisco. He mentions that one of the key parts of his company is the customer service. After a moment’s pause, he says, “Actually, I’d love for you to experience it yourself. Everyone, if you feel like participating, please take out your cell phone and fire off an email to hello@bufferapp.com.”

The audience scrambles to do it. (They already have their phones in their hands from tweeting all of Joel’s wisdom, of course.) Within 2 minutes, we have about 500 emails in the inbox. They test us by asking non-robot questions, telling jokes, and asking for chocolate chip cookie recipes.

The 50 Buffer Happiness Heroes online around the world take a sip of their coffees and teas, stretch out their legs in their homes, local coffee shops or parks, or coworking spaces, and jump on the emails.

On stage, Joel waits. Soon, the hands in the audience start going up as they receive their replies. Within a few minutes, everyone in the audience has their hands up, and smiles on their faces. Some people are laughing to themselves and looking up their Hero on twitter to send a shout out. The guy who wrote in Portuguese thinks to himself how he can’t believe he heard back so quickly, and in his native tongue!

But as we scaled, it became increasingly harder to provide the same level of support. We now have 8.5 million users with 23 customer advocates (not quite the 50 we had envisioned). To maintain a high level of support for our paying customers, we stopped providing email support for free users and built up a help center to allow them to find help themselves.

I have seen three different ways of handling this:

1. The most straightforward option is to hire more people to support the ever-increasing user base. But this is often an option for venture-backed companies only. For example, Slack has roughly 200 people, out of 1,600, on their Customer Experience team. This does not include all customer support role, I believe.

2. Ahrefs charges users $7 for a seven-day trial. Ahrefs went from having freemium to free trials to paid trials. This is quite unheard of in the SaaS space but they made it work. When they switched from having free trials to paid trials, they continued to add the same number of paying customers every month. But they were able to reduce the strain on their customer support team and server and, hence, provide their paying customers a better service.

3. Mailchimp built an easy-to-use free plan and complement it with a comprehensive help center. Mailchimp doesn't provide email, chat, or phone support for free users so that they can focus on helping paying customers. The free plan is so simple (yet useful enough) that most free users rarely need support. Instead of not providing support, Mailchimp made it unnecessary to need support. And if free users do need support, they can get help via Mailchimp's help center. It's amazing to reflect on how I have not reached out for help for my free Mailchimp account even after using it for more than five years.

But an easy-to-use free plan doesn't just happen. And a company cannot sustain itself if every user is using the free plan and doesn't subscribe to a paid plan. For freemium to work successfully, it requires investment in the product, too.

Freemium demands product investment

There are three product things that companies have to work on for freemium to succeed as an acquisition strategy.

First, the free plan has to be polished enough, like Mailchimp's, so that most users can use it successfully without customer support. Most freemium companies only have 3-5 percent paying customers (Buffer has about one percent). In other words, if the free plan is buggy and broken, more than 90 percent of users would need customer support.

Second, the free plan has to continuously improve. There are two forces at play here. One, early adopters tend to have lower expectations for the product and are more willing to use a basic free plan. To attract late adopters, the company has to make the free plan better. Two, as the market becomes more saturated, competition will raise the bar for the free plan. For Buffer, not only do competitors offer more generous free plans, even native platforms like Facebook and Twitter themselves are offering some of our features (e.g. scheduling and messaging) for free. To continue attracting new users, we need to keep making our free plan better.

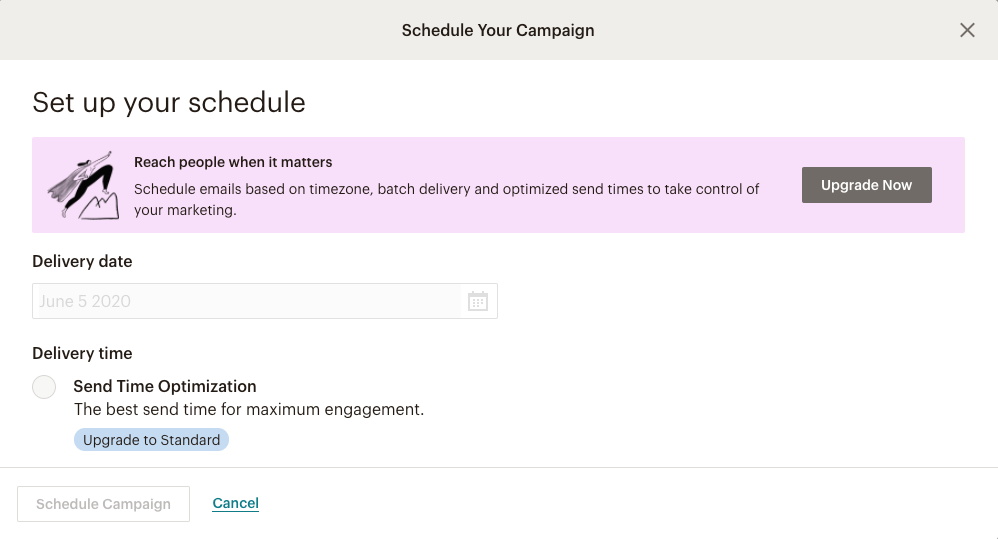

Third, the free plan has to encourage users to upgrade to a paid plan. While it's nice that some free users would spread the word about the product, we ideally want some of them to become paying customers. Therefore, the product has to be built in a way to prompt users to upgrade for advanced features when they are taking relevant actions. For example, if I want to schedule an email campaign, Mailchimp will gently tell me I need to upgrade to a paid plan.

This might seem quite easy to do but when you have many advanced features (which paid plans should), you will have multiple upgrade paths to consider and build for. Such complexities will demand time from your product team.

This might seem quite easy to do but when you have many advanced features (which paid plans should), you will have multiple upgrade paths to consider and build for. Such complexities will demand time from your product team.

Let's take a moment to reflect that what I have shared above is just investment in the free plan—as an acquisition strategy.

The product team also has to invest in the paid plan(s) to generate revenue.

After working with our product team over the past year, I learned that it can be hard to balance the two. From a revenue point-of-view, it makes more sense to add new improvements to the paid plan(s) because that will retain existing customers and attract users to subscribe to a paid plan. When faced with this decision, it can be hard to justify working on the free plan because the free users aren't adding to the bottom line (and word-of-mouth recommendations is hard to track).

Also, making the free plan too good will discourage users to get a paid plan. And it's not easy to determine what's too good or too little. For example, when the New York Times limited free users to 20 articles a month, the New York Times was getting too few subscribers that they had to reduce the limit. This creates another disincentive to invest in the free plan.

Freemium is a company strategy

Essentially, having freemium is a company investment. While it seems like a marketing strategy, it requires customer support and product teams to change the way they do things.

At Buffer, we are intentionally hiring slowly because we want to build a sustainable business without external funding and we aren't aiming for hyper-growth. This has a big influence on how we should approach freemium. We cannot "simply" hire more people to support our growing user base. We also cannot "simply" remove the free plan without angering the majority of our users.

But we can be creative about it.

Companies like Mailchimp and Ahrefs give me hope that there are possible alternatives that are beneficial to both the customers and the company.