Strava's Unbundling and Bundling: Why Didn't It Work (and When It Will)

Alfred Lua / Written on 29 May 2020

Hello there,

Two days ago, I wrote about the packaging experiment I ran at Buffer that almost doubled our trial starts. It is for paying subscribers only. If you're interested, you can get a subscription here.

Continuing the theme on packaging, I'm going to discuss Strava's unbundling and bundling (which have been almost identical to what we have been doing at Buffer).

Strava's and Buffer's unbundling detours

“Gentlemen, there’s only two ways I know of to make money: bundling and unbundling.”

— *Jim Barksdale to a room of *British investment bankers during Netscape's IPO roadshow

Strava is a fitness social media network. Users can log their runs, swims, and rides and give kudos and comment on one another's activities.

Despite having more than 50 million users (unclear how many are active), the 11-year-old company isn't profitable. That's because unlike the major social media networks, Strava doesn't put ads in its app. And it doesn't plan to.

Strava makes money by selling subscriptions for advanced features. They recently did a two-year detour, unbundling their paid product into three smaller products and then bundling them back again. What's interesting is Buffer is doing the same thing. We unbundled our flagship product into two products and bought a third product. Now we are trying to combine them into one.

The detours (and mistakes) are so similar that I think it's worthwhile diving deeper to see what we can learn.

In 2018, Strava unbundled its $7.99/month Strava Premium into three $2.99/month Summit Packs (Training, Analysis, and Safety). In explaining the decision, CEO James Quarles said:

92% of Strava users who set a goal are still active 10 months later, and the obvious response to that data is to make it easier for people to set individual goals. The new a la carte method should make this easier. Another source of inspiration for change was the Strava community itself. Strava spoke to over 10,000 of its users – a mixture of paying and non-paying members – about their thoughts on the service as it stood. A lot of them I’d say were a little bit confused about what Premium entailed and I think they felt it was overdesigned. They thought it was too much or I don’t need all those features. So what we’re doing with this launch of Summit is we want to make that subscription product simpler and more accessible to a broader group of athletes. [Emphasis mine]

When our CEO Joel Gascoigne described our multi-product vision, he said:

With this shift towards a suite of products, we also want to make it easier to pay only for what you need by allowing you to pick and choose the products that fit your stage of the social media journey. We haven’t made any changes to pricing yet and are eager to hear any thoughts or ideas you might have. [Emphasis mine]

Both Strava and Buffer had good intentions. It was theoretically sound. Bundles often feel like a rip-off. Instead of paying a high price for everything, why not let customers pick whatever they want and pay a lower price?

It didn't work out for Strava. Nor for us.

Dedicating Strava to the community is also a commitment to longevity. We are not yet a profitable company and need to become one in order to serve you better. And we have to go about it the right way – honest, transparent and respectful to our athletes.

This means that, starting today, a few of our free features that are especially complex and expensive to maintain, like segment leaderboards, will become subscription features. And from now on, more of our new feature development will be for subscribers – we’ll invest the most in the athletes who have invested in us. We’ve also made subscription more straightforward by removing packs and the brand of Summit. You can now use Strava for free or subscribe, simple.

[Emphasis mine]

We are also in the process of combining our products back into one to simplify things for our customers.

Why didn't it work? Does unbundling not work?

Why didn't unbundling work for Strava or Buffer?

In hindsight, it is because the products work best together and not separately. And because of that, customers want and expect to get them together and not separately.

While this might seem obvious, perhaps in hindsight, two well-known companies have fallen for it. I think there is a great lesson for all of us.

DC Rainmaker, a popular blog on fitness technology, gave a straightforward explanation:

The idea being that Strava could attract some people willing to part with $2.99/month for a single Summit Pack, rather than the full $4.99-$7.99/month for everything (depending on how they paid). At the time, feelings were mixed. Undoubtedly, some people liked the ability to choose a less expensive option with only the features they needed. However, a lot of people were simply confused. As many people pointed out then, the nuances of each offering didn’t really make sense. In theory they might have, but in practice once you started to use the platform you realized the gaps of the groupings. Those gaps might have led folks to upconvert to a full membership…or (more likely), it led folks to stop paying.

[Emphasis mine]

Athletes who would get the Training Pack would also want the Analysis Pack. Strava thought that might encourage them to get both. In the end, they got none.

I find it eerily similar to what we have seen at Buffer.

We unbundled our flagship product into Publish and Analyze. Marketers who would get Publish for their social media marketing would also want Analyze to measure and report their social media results. We thought customers would get both Publish and Analyze. Instead, they also got none. [1]

For both Strava and Buffer, the unbundling didn't make sense for the customers, as much as it did for the business. Strava and Buffer were thinking about upselling customers while customers just wanted to get the tools to get their job done.

Nathan Baschez gave an interesting mathematical explanation on bundling newsletters:

The relationship here is very clear: if people have zero demand for most things in your bundle, it’s a bad idea to try and force a bundle on them. But if people have a little demand for everything, and a lot of demand for some things, then a bundle is a great idea.

It is applicable to Strava and Buffer, too. Athletes want Training Pack and Analysis Pack together, marketers want Publish and Analyze together.

Unbundling would have worked if athletes/marketers strictly want only Training Pack/Publish but have absolutely no desire for Analysis Pack/Analyze. It failed for Strava and Buffer because customers wanted both together.

I think there's also an element of pricing psychology. The lower price of the unbundled products creates an anchoring effect. Even though they would cost the same separately and together, with the anchor set, customers would feel they have to pay extra to get something that should have been included.

Let's walk through two scenarios:

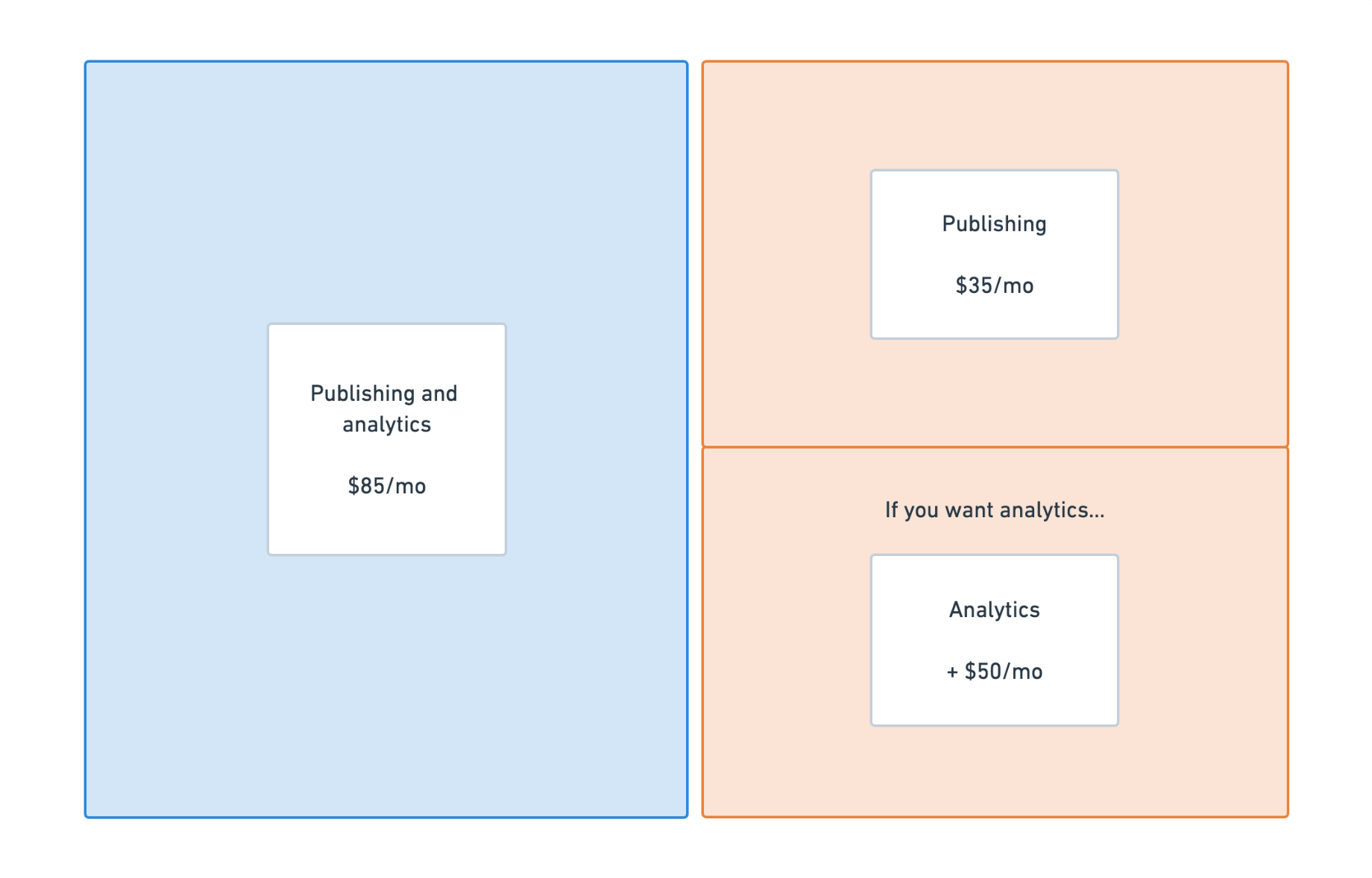

For the first scenario, imagine visiting Buffer's pricing page and see Buffer costs $85/month. You get publishing features and analytics. Cool. Pretty straightforward.

For the second scenario, imagine visiting the same page to see that Publish costs $35/month. You'd have $35 set as an anchor (whether you want to or not because that's how our brain works). Then you would realize you actually have to pay another $50/month for analytics. Wait, why isn't analytics included?

They are exactly the same price but the effects on the mind are entirely different. And these two scenarios are not far from reality. Marketers experience the first scenario when visiting our competitors' website and the second scenario when visiting ours.

Same, same but different

Again, customers are already expecting to get the products together as one. By unbundling, Strava and Buffer made it harder for customers to get them together and made it feel more expensive.

Same, same but different

Again, customers are already expecting to get the products together as one. By unbundling, Strava and Buffer made it harder for customers to get them together and made it feel more expensive.

Good intentions, bad outcomes.

DC Rainmaker gave a nice summary:

Ultimately, for most people, they came away a bit confused and wishing they probably got something else. Not to mention, very few subscription services (almost none) do well with numerous tiers and offerings. Simplification is the name of the game in the subscription world. The more you overthink it, the less users become convinced of it.

That is true for Strava and Buffer. But not for every company.

When does unbundling make sense?

If bundling works when customers expect to get and use the various parts together, unbundling works when customers don't want to get the various parts together.

When does that happen?

When you are selling your products to totally different customers [2].

Intercom's two core products are Outbound Messages and Team Inbox. They are built for two very different types of customers. Outbound Messages is used by product teams who want to proactively reach out to customers to keep them engaged. Team Inbox is used by customer support teams who react to inbound customer messages.

Intercom's two core products are Outbound Messages and Team Inbox. They are built for two very different types of customers. Outbound Messages is used by product teams who want to proactively reach out to customers to keep them engaged. Team Inbox is used by customer support teams who react to inbound customer messages.

There's a pretty clear distinction between the two.

Customer support teams generally don't send outbound messages to customers. Product teams usually don't handle inbound messages. Since they don't expect the two products to be used together, unbundling worked. [3]

Another example is Salesforce. Salesforce is selling software to sales teams, marketing teams, IT teams, and services teams. Because each team has a different need and little overlap with other teams' needs, unbundling makes more sense.

Another example is Salesforce. Salesforce is selling software to sales teams, marketing teams, IT teams, and services teams. Because each team has a different need and little overlap with other teams' needs, unbundling makes more sense.

To be fair, under this premise, Buffer got unbundling partially right. Something I didn't mention above is Buffer's third product, Reply (which has been sunsetted for various reasons). Reply was made for customer support teams while Publish and Analyze are for marketing teams. It wouldn't have made sense to bundle them together because marketing teams don't use Reply and customer support teams don't use Publish and Analyze. And our data showed that.

Similarly, Strava got unbundling partially right. One could split Strava's users into two groups: those who use Strava on their phones (mostly casual athletes) and those who upload their activities from their fitness tracker to Strava (mostly serious athletes). Causal athletes care about their safety and not training analytics. Hence they would want Safety Pack but not Training Pack and Analysis Pack. Serious athletes also care about their safety but their fitness trackers already provide similar safety features. So they would want Training Pack and Analysis Pack but not Safety Pack.

There is an element of timing to unbundling, too.

If we go back 10 years to when social media was new, publishing social media content and managing social media customer service were done by the same person or the same team, usually the marketing team. In that age, a bundled tool for both social media marketing and social media customer service would have made sense.

Over the years, as more people expect customer service on social media, the two functions became more distinct. The marketing team publishes content on social media (and elsewhere) while the customer service team supports customers on social media (and elsewhere). The tool should then be unbundled.

Bundle or unbundle

An interesting consequence of the example above is this: while unbundling of social media marketing and social media customer service is happening, each of them are being bundled to something else.

HubSpot bundled email marketing with social media marketing, Zendesk bundled email customer service with social media customer service.

Whether to bundle or unbundle depends on the company, the industry, and the timing.

I'll leave you with this insightful conversation between Justin Fox of Harvard Business Review, Marc Andreessen, and Jim Barksdale:

**HBR: **Clay Christensen has described this progression in technology from the integrated product to the modular. Jim, in your years in the computer industry you lived that transition from selling these big things at IBM to being part of this totally modularized PC industry. I mean, that sounds sort of like unbundling, but we keep getting new bundles nonetheless, right?

**Barksdale:** Of course, you always are bundling and unbundling. You can’t stand still.

**Andreessen:** One of the patterns I think that you see is that the insurgents often end up reforming themselves into a version of the company they took down. And so, famously, Sun Microsystems took down DEC by unbundling a lot of what it did when it was a huge company. And then Sun sort of reformed itself into what you might call a new DEC — a vertically integrated company which then got taken apart to some extent by Linux and Intel servers.

Oracle is an example. Larry [Ellison] has spoken openly about his attempt to basically recreate IBM by adding applications and services and hardware to what had been an infrastructure software business. And so, ironically, even the people who take down an incumbent through unbundling then come back and try to do the rebundle.

**Barksdale:** Well, because it’s an effective growth strategy. Once you try to grow the business, it’s an easier out to stay focused on your core and then add things to it. And you become a big bundle again.

**Andreessen: **Which then creates a new vulnerability that you didn’t have when you were the insurgent.

[1]: There are some additional nuances here. We wanted customers to be able to mix and match the products they want. But in reality, we didn't make it possible to do that on our website. Customers had to go through a few hoops, which I believe resulted in some of the churn.

[2]: One quick caveat here is it's really hard to build products for multiple types of customers, to market the products, and to support the customers. I generally don't think it's suitable for companies with a small team or no venture capital.

[3]: I'm skipping over a nuance here. Intercom also offers an all-in-one solution with both Outbound Messages and Team Inbox, which seems most suited for marketing teams who look at the entire customer lifecycle. So Intercom is essentially targeting three types of customers.